Bringing macros to Python by abusing type annotations

Posted on

Table of Contents:

Introduction

The desire to bring macros to Python came from my experience with Rust's procedural macros, so we're going to talk about Rust for a second. If you'd like to skip ahead to the Python stuff, click here. Rust is becoming more and more popular by the day for reasons that you've probably heard about:

- It's really fast.

- It has a nice, modern type system.

- It prevents lots of memory errors.

However, my favorite feature of Rust isn't its speed, helpful error messages, etc, but rather its macro system.

There are two types of macros in Rust: declarative and procedural. The real heavy hitters are the procedural macros. The compiler takes your program, parses it into a data structure called an abstract syntax tree (AST), then hands it to a procedural macro. The macro can then do whatever it wants to the AST as long as it hands a valid AST back to the compiler in the end. These are great for code generation. Let's see an example.

Let's say I want to parse some command line arguments into this struct:

struct Opt {

debug: bool,

verbose: u8,

output: PathBuf,

}

There's an app a crate for that: structopt. All we have to do is sprinkle some #[...] things (attributes) into our struct definition. I'm not teaching you Rust right now, so don't worry about the details.

#[derive(StructOpt, Debug)]

#[structopt(name = "basic")]

struct Opt {

// Enable debug mode

#[structopt(short = "d", long = "debug")]

debug: bool,

// Set verbosity

#[structopt(short = "v", long = "verbose", parse(from_occurrences))]

verbose: u8,

// Output file

#[structopt(short = "o", long = "output", parse(from_os_str))]

output: PathBuf,

}

The compiler will see the macro and generate all of the code needed to parse command line arguments into the struct Opt.

fn main() {

let opt = Opt::from_args(); // thank you structopt!

println!("{:?}", opt);

}

That's pretty handy, right? All you had to do was define which arguments you were expecting, and the macro took care of the rest!

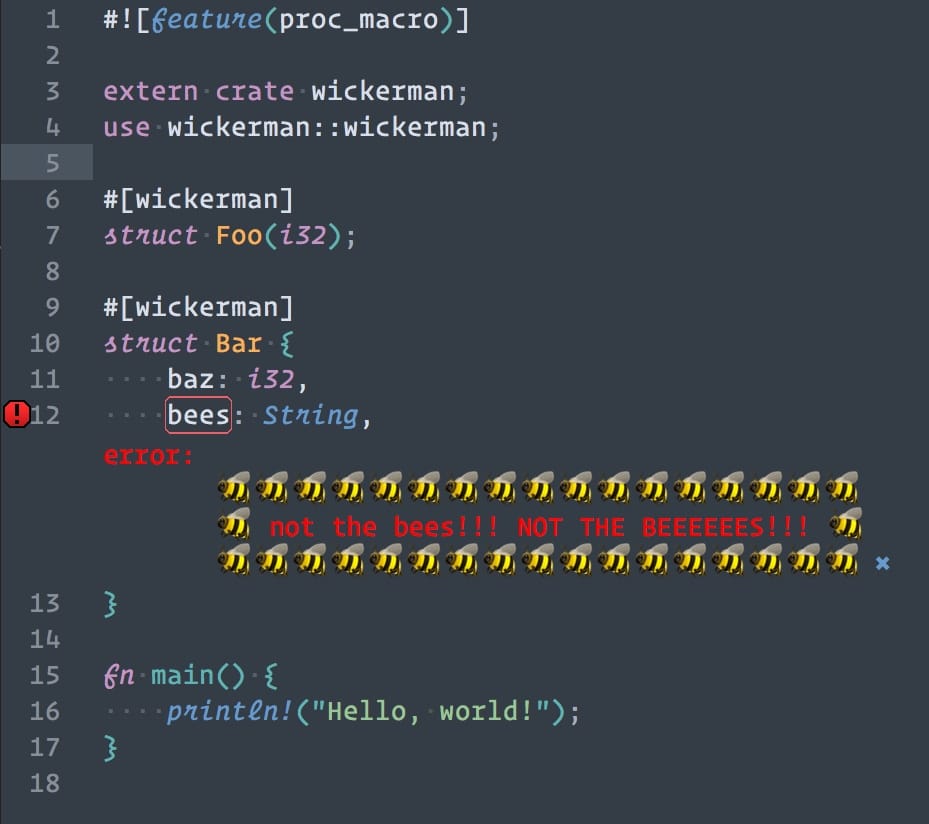

You can also do less useful things, like blow up your editor with error messages from The Wickerman.

If you'd like to read about that, you can do so here: link to shameless plug

So, here's the million dollar question: Can you make Rust-like macros in Python?

What am I trying to build?

Let's unpack what it means to have Rust-like macros in Python. I'll examine this with three questions:

- What is a macro?

- What's special about Rust macros?

- What do my Python macros need to do?

What is a macro?

Usually a macro provides a shorthand for something. In this case, a macro would be a function that takes your class definition as input, reads it, generates some code for you, and returns a new class with the generated code.

What's special about Rust macros?

A primitive macro system operates by simply replacing one bit of text with another i.e. replacing PY_VERSION with 3.6.5. Rust's (procedural) macros operate by performing operations on the logical structure of your code (the AST). Rust's macros can be applied to struct, enum, function, and module declarations. Furthermore, macros can be applied to the members of structs/enums, like in the example above.

What do my macros need to do?

I want the macros to provide a convenient alternative to something tedious. That said, this is only a proof of concept, so the problems I'm solving will be a little contrived. I'm going to keep the scope narrow and apply my macros only to class definitions. I still want to be able to configure how the macro operates on individual class/instance attributes, though.

Research

I set out to determine if it was even possible to do what I wanted to do. I knew that I could apply a decorator to a class, so that part was covered. The part that would be trickier is attaching information to individual class or instance attributes. Eventually something jumped out at me. Take a look:

class MyClass:

foo: int # <-- information attached to "foo"!

A type annotation looks like what I want to do, but what if I want to put something other than int, str, List[int], etc in the annotation? I looked around and remembered that in some cases you put a string where you would normally put the annotation, like so:

class MyClass:

foo: "MyClass"

This allows you to use types that haven't been defined yet as an annotation, like when you're defining a recursive data structure. So the type annotation doesn't have to be an actual class, it can also be a string. Well, what can go in this string? Anything, apparently!

If you read PEP 484 (relevent section here) you'll see that the type annotation can actually be any valid Python expression. The implications of that didn't really sink in at first, so we'll come back to it later.

At this point I realized that I could stick arbitrary information in a string and attach it to a variable. Sure, this wouldn't play well with type checkers, or really any sane use case for type annotations, but no one really uses type annotations, right? All the cool kids are doing it, no one will get hurt. Don't be such a square!

Ok, so I can store information in the annotations, but how do I read it at some later time? To the Python data model! I dove into the data model to learn about the guts of Python. I actually got my first CPython contribution from this endeavor.

I'm still waiting for my core developer invitation. Anyway, I learned that annotations are stored in the __annotations__ attribute. The __annotations__ attribute is a dictionary where the keys are the attribute names, and the values are the annotations. Consider the following class:

class MyClass:

foo: int

bar: "anything"

The contents of __annotations__ would look like this:

>>> MyClass.__annotations__

{

'foo': <class 'int'>,

'bar': 'anything',

}

Now I know I can store information in type annotations, and I know how to retrieve that information. All that's left is messing with abstract syntax trees.

Abstract syntax trees

Parsing code into an abstract syntax tree is something that Python does when it compiles your source code into bytecode. In fact, the ast module contains all of the data structures, or "nodes", that your Python code can be parsed into. The module documentation doesn't do a great job of making it clear which nodes exist or what their attributes are. Instead, I recommend this page if you want to see what's at your disposal. For those of you that have never seen or heard of an abstract syntax tree, I'll show you the basics by building up the AST of a small code snippet.

Let's start with a really basic code snippet: 10. This is just the number 10. Exciting. To represent this you create an instance of ast.Num:

num = ast.Num(n=10)

What about -10? That's more complicated because - is an operator, so -10 is not just ast.Num(n=-10). Instead, it's this:

num = ast.UnaryOp(op=ast.USub(), operand=ast.Num(n=10))

What if I want to assign -10 to a variable x? That's an assignment, so we'll need an ast.Assign node, but how do you handle x? Any time you reference a variable, you need an ast.Name node. Each Name has an id, which is the name of the variable, and a context, ctx, which indicates whether you're getting (ast.Load()) or setting (ast.Store()) the value of the variable. Putting all of that together, the assignment looks like this:

# x = -10

num_node = ast.UnaryOp(op=ast.USub(), operand=ast.Num(n=10))

x_node = ast.Name(id="x", ctx=ast.Store())

assign_node = ast.Assign(targets=[x_node], value=num_node)

That's really all there is to it, so hopefully you get the idea. Building up anything more complicated than that is just a matter of putting the right nodes together. If you want to play around with this, you can also do the reverse:

>>> ast.parse("x = -10")

<_ast.Module object at 0x10f5f3208>

Note that any time you use ast.parse, the result will be a module. The Assign node will be in the body of the Module.

>>> module = ast.parse("x = -10")

>>> module.body[0]

<_ast.Assign object at 0x101ad4d68>

As you can see, the string representation isn't super helpful. Some libraries that provide useful tools for dealing with ASTs in Python (and printing them in more useful ways) are astor and astpretty. Here's the same thing using astpretty:

>>> import ast

>>> from astpretty import pprint

>>> pprint(ast.parse("x = -10"))

Module(

body=[

Assign(

lineno=1,

col_offset=0,

targets=[Name(lineno=1, col_offset=0, id='x', ctx=Store())],

value=UnaryOp(

lineno=1,

col_offset=4,

op=USub(),

operand=Num(lineno=1, col_offset=5, n=10),

),

),

],

)

Now that I have all of the pieces in place (decorators, type annotations, and ASTs), I can show you what you can do with all of this!

Example 1 - @inrange

For my first trick, I've created a decorator, @inrange. If you place the annotation "0 < foo < 3" on a class variable named foo, the decorator will generate a class with a property named foo that only accepts values in the range (0, 3) exclusive. Consider the following class definition:

@inrange

class MyClass:

var: "0 < var < 10"

The decorator will generate a class equivalent to this:

class MyClass:

var: "0 < var < 10"

def __init__(self):

self._var = None

@property

def var(self):

return self._var

@var.setter

def var(self, new_value):

if 0 < new_value < 10:

self._var = new_value

else:

raise ValueError

Here's what it looks like in action:

>>> @inrange

... class MyClass:

... foo: "0 < foo < 5"

...

>>> bar = MyClass()

>>> bar.foo = 1 # no problems here!

>>> bar.foo = 6 # oh no, greater than 5!

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<input>", line 1, in <module>

bar.foo = 6

File "/Users/zmitchell/Projects/annotation-abuse/annotation_abuse/asts.py", line 1, in foo_setter

import ast

ValueError: value outside of range 0 < foo < 5

There are some weird things here. Note that the line above the ValueError says import ast, even though I didn't import the ast module in the shell. I use the ast module to generate code, but I don't really know what that's about. The error message also says that the error occurs in foo_setter, even though you don't have a function called foo_setter. This is a result of the way that I make the properties. For a variable named foo I create the functions foo_getter and foo_setter, create a property with property(foo_getter, foo_setter), then bind that to the attribute foo.

Here are the broad strokes of how this works, assuming you have a class named MyClass and you've annotated a class variable named var:

- Grab the annotation from

MyClass.__annotations__["var"]. - Grab the endpoints of the range from the annotation.

- Generate ASTs for the getter and setter of

var. - Compile the ASTs to Python functions.

- Create a property from the compiled functions.

- Bind the property to the class.

- Create an AST for the

__init__method. - Compile the

__init__AST to a function. - Bind the

__init__function to the class.

Each class variable with an annotation is represented by a MacroItem:

class MacroItem:

def __init__(self, var_name, annotation):

self.var = var_name

self.annotation = annotation

self.lower = None

self.upper = None

self.getter = None

self.setter = None

self.init_stmt = None

These MacroItems get passed to the functions that extract information from the annotation, generate ASTs, etc. For example, here is the function that generates a getter from a MacroItem:

def getter(item):

func_name = f"{item.var}_getter"

self_arg = arg(arg="self", annotation=None)

func_args = arguments(

args=[self_arg],

kwonlyargs=[],

vararg=None,

kwarg=None,

defaults=[],

kw_defaults=[],

)

inst_var = Attribute(

value=Name(id="self", ctx=ast.Load()), attr=f"_{item.var}", ctx=ast.Load()

)

ret_stmt = Return(value=inst_var)

func_node = FunctionDef(

name=func_name,

args=func_args,

body=[ret_stmt],

decorator_list=[],

returns=None,

)

mod_node = Module(body=[func_node])

return _ast_to_func(mod_node, func_name)

Note that you can't compile a FunctionDef node by itself, you have to wrap it in a Module node first. Here is the magic that compiles an AST into a function.

def ast_to_func(node, name):

ast.fix_missing_locations(node)

code = compile(node, __file__, "exec")

context = {}

exec(code, globals(), context)

return context[name]

This definitively shows that you can make Rust-like macros in Python. That's not to say that it's easy or recommended though. Constructing an AST is definitely (the AST for -10 is ~4x as many characters as 10), so it can be tedious. It was a fun exercise, but I'll show you a better way to make code-generating macros.

Example 2 - @notify

For my next trick, I've made a decorator @notify that will print a message to the terminal when you try to assign a new value to a class or instance variable marked with a specific annotation.

@notify

class MyClass:

var: "this one" = 5

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

self.y: "this one" = 0

If you try typing that into the Python shell, it will crash. If you're working in the shell and you decorate a class with @notify that has an __init__ method, it will crash. I have no idea what that's about. If you want to try this in the shell, put the annotation on a class variable. You can put whatever you want into a file though, and it will work just fine. Let's see what happens when you try to assign to a variable you've marked.

from annotation_abuse.notify import notify

@notify

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, x):

self.x = x

self.y: "this one" = 0

if __name__ == "__main__":

foo = MyClass()

foo.y = 1

Run this, and you'll see a familiar face:

_________________________________________________

/ \

| It looks like you're trying to update MyClass.y |

| from "0" to "1". |

| Would you like some help with that? |

\_________________________________________________/

\

\

__

/ \

| |

@ @

|| |/

|| ||

|\_/|

\___/

Let Clippy update the value? (y/n):

If you say yes:

Let Clippy update the value? (y/n): y

_____________

/ \

| No problem! |

\_____________/

\

\

__

/ \

| |

@ @

|| |/

|| ||

|\_/|

\___/

If you say no:

Let Clippy update the value? (y/n): n

______

/ \

| FINE |

\______/

\

\

__

/ \

\ /

@ @

|| |/

|| ||

|\_/|

\___/

This example was easier in some ways, but harder in others. I'm not constructing ASTs, so the code is much less verbose. On the other hand, I'm overriding MyClass.__setattr__ in order to intercept writes to the marked variables. Boy oh boy was that a can of worms.

Annotations on class variables can be pulled from MyClass.__annotations__ (like the previous example), but annotations that appear inside __init__ don't show up there. To find those annotations, I parse __init__ into an AST (look, I'm sorry, I couldn't help myself), then traverse the tree looking for things that have the annotation "this one".

Once I've built a list of attributes to watch, I need to intercept writes to those attributes. I knew I could intercept writes to certain attributes by replacing them with properties, but I wondered if there was a different way to do it (just for kicks). I went back to the documentation for the data model and read up on __setattr__. The __setattr__ method gets called when you try to set the value of an attribute, so overriding __setattr__ will let me intercept writes to the attributes I care about.

I generate a new __setattr__ as a closure, as you can see below:

def make_setattr(cls, var_names):

def new_setattr(self, attr_name, new_value):

if attr_name not in var_names:

setattr(self, attr_name, new_value)

return

# The instance variable will be set for the first time during

# __init__, but we don't want to prompt the user on instantiation.

if attr_name not in self.__dict__.keys():

setattr(self, attr_name, new_value)

return

current_value = self.__dict__[attr_name]

attr = cls.__name__ + "." + attr_name

show_message(attr, current_value, new_value)

user_resp = prompt_user()

if user_resp == Response.YES:

no_problem_message()

setattr(self, attr_name, new_value)

elif user_resp == Response.NO:

angry_message()

return new_setattr

I model the user's response with an enum, storing the acceptable responses in the value of each enum variant to make it easier to validate the response. The Response.INVALID case is handled in the prompt_user function. Rust taught me how powerful enums can be, so now I want to use them everywhere!

class Response(Enum):

YES = ["y", "Y", "yes", "Yes", "YES"]

NO = ["n", "N", "no", "No", "NO"]

INVALID = ""

def interpret_resp(text):

"""Interpret the user's response."""

resp = text.strip()

if resp in Response.YES.value:

return Response.YES

elif resp in Response.NO.value:

return Response.NO

else:

return Response.INVALID

One thing I found confusing during this process is that lots of documentation surrounding __setattr__ says that you should call the super class's __setattr__ when you're overriding __setattr__, and most documentation just cites object.__setattr__(self, name, value). I found the documentation around this to be sparse, at best, and I only accidentally stumbled onto a solution. Here's what happened.

My working solution uses setattr, so let's replace setattr(self, attr_name, new_value) with object.__setattr__(self, attr_name, new_value):

TypeError: can't apply this __setattr__ to type object

Huh? I searched the internet for what this error message meant, and my understanding is that it's related to setting new attributes on built-in types. So, that tells me that I was accidentally trying to set a new attribute on object. Using super(cls, self).__setattr__ gives you the same error.

Let's try super().__setattr__(self, attr_name, new_value) and see if it just sorts itself out:

RuntimeError: super(): __class__ cell not found

Ok, this one actually makes sense (see here). In short, I'm calling super() in a function that's not bound to a class when it's defined, so it doesn't know what class it belongs to. I think.

Eventually I just tried setattr and it worked. I was pressed for time preparing this for a lightning talk, so I didn't have time to really dig into the issue. If someone knows what's going on, let me know!

Taking it to the next level

I presented the two examples above in a lightning talk at PyOhio 2018. The reception was good, and I ended up talking to Dan Lindeman and Jace Browning in an open space about alternative uses for type annotations. As we were talking, we came to a realization.

Remember earlier when I said that a type annotation can be any valid Python expression? Well, lots of things are valid Python expressions. Say, for instance, a lambda. Take a look:

>>> class MyClass:

... foo: lambda x: 0 < x < 5

...

>>> MyClass.__annotations__["foo"](3)

True

If you're not amazed that this is possible, check your pulse. This is saying that you can attach entire functions to an attribute, not just a string or a type! It's like every variable carries around a little suitcase that can hold (almost) anything you want!

I think I'm done with this particular project for now, but I'm sure there's all kinds of terrible wonderful things you can do with this. If you have any ideas, I'd love to hear them! The code for all of this can be found on my GitHub at zmitchell/annotation-abuse.