Composition: the feature I've wanted in Flox since I joined the company

Posted on

Table of Contents:

Yes, this post is going to be about Flox, my employer, but this isn't an advertisement. This is me, both an engineer and a user, describing why I think a new feature I worked on is interesting, how it can change the way you develop your software, and what it was like to take point on the feature. We called this feature "composition", and it allows you to build developer environments in a modular way out of other developer environments. It was initially released in Flox 1.4.0, and rounded out in 1.4.1. It's really cool.

The feature

Flox environments

The central abstraction in Flox is the "environment", which is a generalization of the "developer environment" since Flox environments are useful for more than just local development.

For example, you can use a Flox environment situated in your home directory (we treat this specially and call it the default environment) to use Flox as a system-wide package manager, replacing brew or whatever your package manager of choice is.

There are no containers or VMs involved. When you "activate" an environment you're placed into a new subshell (by default) whose environment is configured very carefully. Once you're inside the environment, you have access to the packages, environment variables, services, etc that you've defined as part of your environment. Environments also have configurable startup scripts that run when activating the environment.

If you want to stay in your current shell rather than entering a new subshell, there are ways to make Flox spit out shell code that you can then eval.

In fact, this is how you configure your shell to activate your default environment for every new shell:

eval "$(flox activate -d ~ -m run)"

Flox uses Nix under the hood for reproducibility (no, we aren't just calling nix develop or nix shell under the hood1), which means that we can enumerate and lock all of the packages, environment variables, scripts, etc that go into an environment, store that in a lockfile, and reproducibly build it on another machine.

Combining environments

Since Flox environments are just shells, you can nest them. This allows you to "layer" environments. This also that means your developer environment can context switch with you.

Say you work on a web service and you have an environment stored in git along with your source code.

When you start work you cd myrepo followed by flox activate.

Now you're ready to work.

You discover a networking bug, and want to investigate further, so you flox activate --remote your_user/net_tools, an environment you've pushed to FloxHub that contains some extra network debugging tools.

You're now in a nested subshell with access to both your development tools, and your debugging tools.

Once you're done debugging, you exit and you're back to the shell that just has your development tools.

The first time you do that and see how easy it is, it's a "hell yeah" moment. This makes context switching pretty painless, and it makes it possible to build up a tech stack from building blocks. In this case you're combining environments by layering them in succession.

Let's say you have separate environments for your development tools (dev), running a Postgres server (postgres), and running a Caddy server as a remote proxy (caddy).

In order to get access to all of these at the same time, you need to flox activate dev, flox activate postgres, and flox activate caddy every time you want to do work.

There are some other drawbacks here, like a tool provided by the caddy environment shadowing one from the dev environment because it appears earlier in PATH (it was activated later).

This makes layering suitable for ad-hoc tasks, but less well suited for building up a developer environment from building-block environments. That's where composition comes in, and it's so cool that it gives me nerd-glee that it exists.

Composition

The idea behind the composition feature is that you can merge environments rather than layering them. A high-level documentation page and a tutorial are available in the official documentation (both written by me, feedback welcome).

Composing environments is trivially easy.

You add the following section to your manifest.toml (our config file), listing the environments you want to merge:

[include]

# Later entries are given higher priority during the merge

environments = [

# An environment present at a relative path

{ dir = "path/to/env" },

# An environment on FloxHub containing a Rust toolchain

{ remote = "zmitchell/rust" }

]

This is so cool. You can now prepare independent developer environments for different contexts, and piece them together to cover the majority of your needs for new projects. Installing Python and your Python package manager of choice isn't the interesting part of working on a project, it's the stuff that makes the project unique. Define a Python environment that contains the interpreter, package manager, etc that you can bring to every new Python project, then focus on unique parts.

Consider this scenario: you're working on a web service that depends on a database and a Rust toolchain to develop the service itself. Here's what all of that looks like:

[include]

environments = [

{ remote = "zmitchell/rust" },

{ remote = "zmitchell/postgres" }

]

The other day one of my coworkers put together a Kafka environment and a Karapace environment (it's a Kafka schema registry thing, idk, I'm not a Kafka person), which you can then configure with environment variables:

version = 1

[vars]

KAFKA_MODE = "kraft-combined"

KAFKA_NODE_ID = "1"

KAFKA_HOST = "172.30.38.117"

KAFKA_PORT = "9092"

KRAFT_CONTROLLER_PORT = "9093"

KAFKA_CLUSTER_ID = "EBzt0KoZR5ynZ9hTiJQuFA"

KAFKA_REPLICATION_FACTOR = "1"

KAFKA_NUM_PARTITIONS = "1"

KAFKA_HEAP_OPTS = "-Xmx512M -Xms512M"

REGISTRY_HOST = "172.30.38.117"

REGISTRY_PORT = "8081"

REST_HOST = "172.30.38.117"

REST_PORT = "8082"

LOG_LEVEL = "INFO"

[include]

environments = [

{ remote = "barstoolbluz/kafka-basic-patch" },

{ remote = "barstoolbluz/karapace-basic-patch" }

]

How it works

When the environment is built, the manifests of all of the "included" environments will be merged, and then the manifest of the "composing" environment will be merged into that.

This creates a "merged" manifest from which we lock and build a "composed" environment.

You don't edit this merged manifest directly, but you can surface it via flox list -c 2, which will print out the merged manifest if one exists, or the normal manifest if a merged manifest doesn't exist.

In case of conflicts between data contained in different manifests, entries later in the include.environments array are given higher priority, and the composing environment's manifest takes the highest priority.

This allows you to fix situations where one environment shadows a package/variable provided by another: the composing environment can redeclare the package/variable to override and fix the situation.

As part of the design process we discussed more granular overrides, but we decided to keep things simple for this first pass.

The included environments will likely see updates over time, so we also provide the flox include upgrade command to pull in the latest manifests, re-merge, and build the environment.

Ok, nifty, let's talk about how it affects your workflow.

My new workflow

I have ADHD, which means I start new projects more often than most people, which means that I probably feel the pain of setting up developer environments for new projects more often than most people. My development workflow has changed over the years, but it has gone through these rough phases: YOLO, Nix, and now Flox.

The YOLO workflow was basically Rust installed via rustup, Python installed via pyenv installed via brew, and then random other dependencies installed through brew as well.

I used containers at work, but always found them kind of a pain in the ass for side projects between needing to SSH into them, mount in directories, expose ports, deal with inevitable file permissions issues because I fucked something up, etc. So, while I acknowledge that containers exist and work for a lot of people, I skipped that phase for personal projects and went straight to Nix.

The Nix workflow was basically copying and pasting flake templates from one project to the next. That was also kind of a pain in the ass, but it was a one-time upfront pain in the ass when setting up a new project, and then everything tended to just work.

Then, once Flox got to a point that I was comfortable using it for my local development, I bootstrapped new projects with one command: flox pull --copy zmitchell/rust.

This gives me a copy of my Rust toolchain environment that I can then extend with project-specific dependencies, disconnected from the copy that's stored on FloxHub.

That's how I've worked for a while now, and it works well.

There are no pains in my ass with this workflow, but it does mean that I have a handful of projects using essentially the same tools but with no connection to one another.

Furthermore, since these projects are disconnected from each other, it's possible that I have multiple copies of very similar toolchains in my Nix store, taking up space.

This also means that if I add one package to my Rust toolchain (e.g. pkg-config), none of these disconnected projects will get that update.

With composition I could add pkg-config to zmitchell/rust once, and then I'll get it the next time I flox include upgrade an environment that includes zmitchell/rust.

This also means that if I go flox include upgrade any environments that use zmitchell/rust, I'll only have one copy of that toolchain on my system rather than N.

If I want to pull updates to one of the enviroments (e.g. zmitchell/rust), but not the others, I can do that too.

Currently, with composition, my initial setup is slightly longer, but it's cleaner and let's me retain the connection to and history of the original environment on FloxHub.

Now I flox init, followed by flox edit to add this:

[include]

environments = [

{ remote = "zmitchell/rust" }

]

With composition, my manifest contains the list of environments that I want to build off of, and then only the very specific things I want for this project.

That keeps the manifest.toml concise, and allows for a separation of concerns not really possible with other tools.

We have lots of ideas for how to make this workflow better.

For instance, I have an open ticket for creating a flox include add command (or something like it) that will let me include zmitchell/rust from the command line rather than editing it in manually.

We also want to add the ability to pin remote environments, but there's design work to be done before we implement that.

Why this matters

The reason this is important is that it's now possible and easy to build developer environments out of reusable, composable building blocks. Think of how much time and effort that saves! If I set up a Rust toolchain, a Python toolchain, etc why should I ever do that same work again? Just include it and add in your project specifics.

This isn't the main use case for me, but we've also already used this feature to provide support to some of our users e.g. they want a feature that doesn't exist yet, but we give them an environment to include whose setup script does the thing they're asking for.

My coworkers and I all had the same experience using this for the first time. We all tried it out, and it just worked, and we said "hell yeah."

What it was like to work on it

So, with all of that out of the way, let's get a little bit meta and reflect on what it was like to work on it.

Work plan

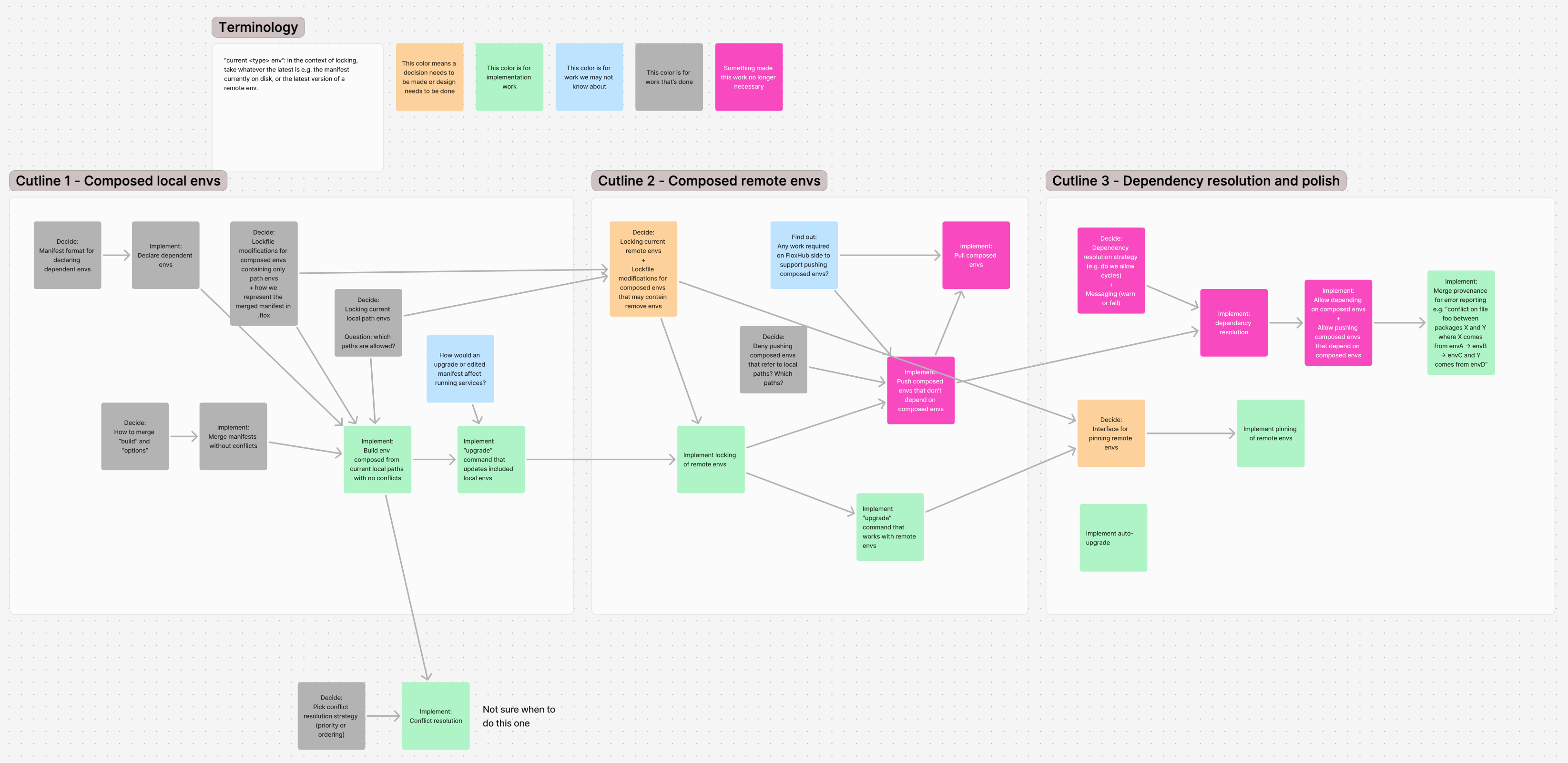

I've often wished that projects had something like a directed graph of what the work looks like so that I can see how much there is in total, how much has been completed, how much is remaining, where decisions will block implementation, etc. Since I was the lead for this feature, I decided to make one in Figma.

I tried to color code "sticky notes" by their completion status and whether they were implementation work or decisions. No one else used this (it was mainly for me), but it did help defer certain decisions in favor of getting started on the engineering work, which was helpful for getting it out the door faster. To be clear, the actual work was split out into workable GitHub issues, but the graph helped keep an eye on the high level progress and direction.

Design decisions

For this first pass the user experience isn't perfect, but I think it laid the ground work well. The main design choice was whether to lock and record the manifests of the included environments at merge-time. If you lock and record the manifests you can re-merge at any time without needing to fetch those manifests again, allowing you to decouple "install a new package" from "get me the latest manifests". If you don't lock and record the manifests, you're required to fetch the latest manifests any time you build the environment, which gives you an auto-fetch-and-upgrade mechanism out of the box.

I argued for the lock-and-record case because the other case allows you to get in weird situations (I'll omit the details for the sake of time), but it does mean that some things you wish were automatic are currently manual (e.g. you need to run flox include upgrade to get updates to included environment manifests).

That said, the ground work is laid for an intentional auto-upgrade mechanism.

The next big design question was how to implement merging the manifests. We considered two main options.

Our manifest is currently represented with a strongly-typed Manifest struct (the CLI is written in Rust), so one option was to manually write out the traversal of the manifest struct, with all the friction that entails due to the nested structure and strong typing.

The other option was to treat the TOML like JSON, and merge serde_json::Value structs (this is a generic JSON object, for you non-Rust people).

Eventually we landed on the manual, strongly-typed option because some of the manifest fields make more sense to overwrite during the merge rather than strictly merging.

One example of this is the list of command line arguments to use as the Cmd when you bundle up a Flox environment into a container (merging ["bash", "foo"] with ["bash", "bar"] to create ["bash", "foo", "bash", "bar"] is probably not what a user expects).

Looking ahead to some future work where we want to provide structured information about the diff between two manifests, it may be worth creating a procedural macro that can automatically generate a visitor pattern trait for comparing two manifests. That would look something like this:

trait ManifestCompareVisitor {

fn compare_install(&mut self, install_left: &Install, install_right: &Install);

fn compare_vars(&mut self, vars_left: &Vars, vars_right: &Vars);

...

}

This would allow us to have one interface that can be used for both merging and diffing.

Conclusion

If you've made it this far, thanks for reading, no one has ever accused me of having too little to say. Give Flox a try, let me know what you think about this composition feature, etc. Is it interesting to hear about what the work process is like? I've never really written about that before, but found it kind of cathartic.

We basically wrote our shell-handling code from scratch, and I have the scars to prove it. If you use Flox with Zsh, you owe me and my team a collective drink. I think 10 different lifecycle files ({~, /etc/}.{zshenv, zlogin, zlogout, zprofile, zshrc}) is a bit much.

It's one of my pet peeves that flox list --config (1) doesn't list anything, it prints one thing, (2) the thing we're printing is the "manifest", not the "config", and (3) we have a separate thing called "config" that this command doesn't print. Humbug.